Tax-Efficient Retirement Withdrawal Strategies to Combat the RMD Tax Tsunami

We earn a commission from the offers on this page, which influences which offers are displayed and how and where the offers appear. Learn more here.

TL;DR

Retirees have up to three types of accounts to draw from in retirement: traditional retirement accounts, Roth retirement accounts, and taxable accounts. Each account type is taxed differently. By choosing which accounts to draw from each year, retirees have the flexibility to manage when they’ll pay taxes and how much they’ll pay.

The traditional rule of thumb states that retirees should first spend from taxable accounts, then from traditional retirement accounts, and finally from Roth retirement accounts. The appeal to this approach is that it allows retirees to keep as much money as possible in tax-advantaged accounts for as long as possible. It’s also easy to follow.

While it may be counterintuitive, the traditional rule of thumb often results in retirees paying more taxes than they should. Why? It ignores what I call the RMD tax tsunami. By deferring withdrawals from traditional retirement accounts, retirees build up wealth in these accounts until the floodgates open when RMDs begin. The result is often a sudden increase in a retiree’s marginal tax rates and tax liability.

A more tax-efficient approach involves spending from multiple account types each year in retirement to smooth out the tax liability. Alternatively, retirees can execute partial Roth IRA conversions, which helps smooth out the tax liability while at the same time keeping as much money as possible in tax-advantaged accounts. Tax smoothing can increase a retiree’s after-tax spending, increase their after-tax wealth, or both.

In What Order Should You Draw Down Your Retirement Accounts?

The question retirees often ask is what order should they draw down their retirement accounts. Implicit in this question is that one should exhaust one account type, say taxable, before drawing from the next type. As we’ll see, this approach is rarely ideal. And yet, it’s the standard approach often recommended by advisors and used in financial planning tools.

The Rule of Thumb

To simplify what can be a complicated tax analysis, advisors often suggest the following order of withdrawals: taxable accounts, followed by tax-deferred accounts, followed by Roth retirement accounts. This approach was recommended as far back as 2002 in an American Association of Individual Investors’ article. More recently, Vanguard has recommended this approach. This rule of thumb is often incorporated into retirement planning tools, such as New Retirement.

Financial Planning Software

Financial planning software often defaults to a simple order of withdraws for lack of a better alternative. The optimal order of withdrawal will vary from person to person, and can even change over time for the same person. Thus, good financial planning software like New Retirement will give users features to model their optimal withdrawal strategy. Some tools, such as Maxifi and OnTrajectory, offer tools to optimize the withdrawal order by clicking a button. The problem is that the results still deplete all of one type of account at a time. This is rarely, if ever, optimal.

In addition to its simplicity, the rule of thumb has two other benefits. First, it leaves money in tax-advantage accounts until it’s needed or RMDs require its withdrawal. We get the tax advantages retirement accounts offer for a decade or more into retirement.

Second, spending taxable assets first reduces over time the taxable dividends and interest that these accounts generate.

In the words of Shakespeare, however, “Why then, can one desire too much of a good thing?” It turns out that while tax deferral is an excellent strategy to a point, deferring too much income can result in paying more taxes over a lifetime.

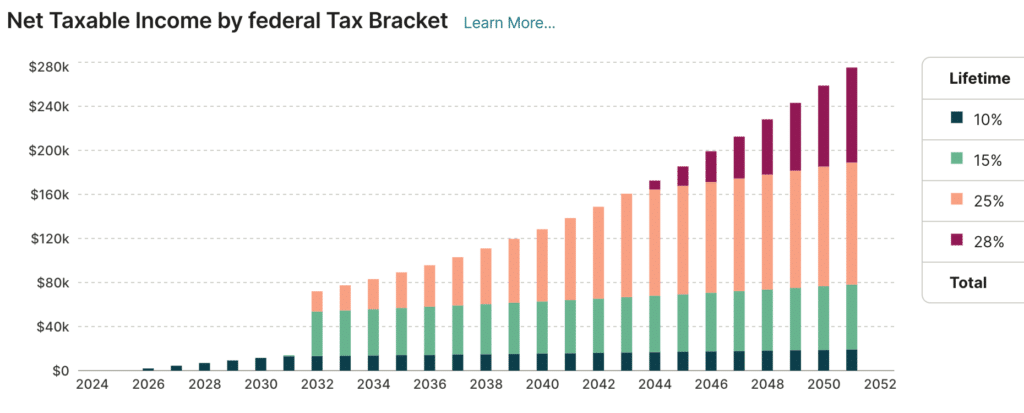

As an example, let’s assume a 65-year-old retiree has $750,000 in a taxable account and $750,000 in a traditional IRA (tIRA). If we factor in Social Security and follow the traditional rule of thumb in order of withdrawals, we can see their taxable income by tax bracket over a 30-year retirement.

Before RMDs kick in, this retiree pays very little if anything in federal income tax. Deductions offset most of the Social Security benefits and capital gains from withdrawals from the taxable account. When RMDs start in 2032, however, the tax brackets jump, eventually rising to the 28% bracket.

The tax deferrals in the early years of retirement prove too much of a good thing.

We could flip this result by spending tax-deferred monies first, and only then our taxable investments. Unfortunately, this strategy often creates the worst of all worlds. We quickly lose the benefits of tax-advantaged accounts as we deplete them first. At the same time, we push our income into higher tax brackets in the early years of retirement. It’s a heads we lose, tails we lose even more situation.

Fortunately, we have two related concepts to address these issues: Tax Smoothing and Tax-Free Harvesting.

Marginal Tax Brackets vs Marginal Tax Rates

Marginal Tax Rates should be the focus in any analysis of tax-efficient withdrawal strategies. Unlike Marginal Tax Brackets, which focus solely on the highest income tax bracket reached each year, Marginal Tax Rates account for the effect income has on the taxation of Social Security benefits, the taxation of capital gains, Affordable Care Act credits, and the cost of Medicare. At the same time, Marginal Tax Brackets are a useful starting point when building out a withdrawal strategy.

Tax Smoothing

As we saw from the image above, a retiree’s tax liability is often lopsided. Many retirees can keep their taxes quite low in the early years of retirement, in some cases at zero, by drawing primarily from taxable accounts. When RMDs begin, and with Social Security benefits coming in, retirees then see their tax liability skyrocket. This is often the case when retirees follow the traditional rule of thumb of spending first from taxable accounts, then traditional, and finally from Roth accounts.

To address this imbalance, we need to find what certified financial planner Michael Kitces describes as our tax equilibrium. Here’s how he describes a retiree’s tax equilibrium:

As a result, the optimal strategy for managing tax-deferred growth, and the potentially substantial build-up of pre-tax assets (from unrealized capital gains to traditional IRAs and 401(k) plans), is to defer enough to avoid high tax rates now, but not so much as to cause much higher tax rates in the future. In essence, it’s about finding the equilibrium point – like the balancing point on a seesaw – where enough income is created or recognized now to avoid “too much” in the future, but not so much is drawn into the present that it would have been better to just defer the income and wait until later when tax rates might have been lower!

To prepare for the RMD tax tsunami, retirees can take advantage of the low tax brackets in early retirement by shifting forward some of the taxes that otherwise wouldn’t be due until RMDs begin. They can do this by drawing from tIRAs, at least in part. They can also do this through partial Roth IRA conversions. The question here is how much.

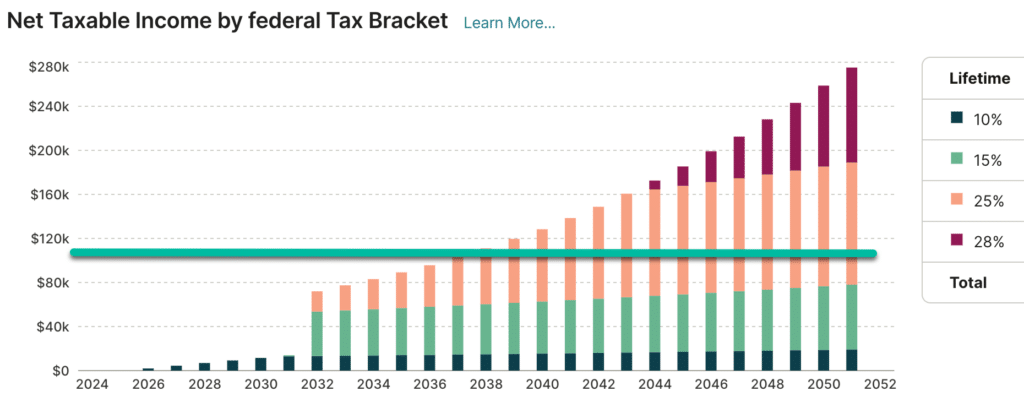

The image below is a rough approximation of the tax equilibrium for our hypothetical retiree.

If we increase our taxable income in the early years up to the 15% or perhaps 25% tax bracket, we can lower our taxable income in later years down from the 28% bracket. We may also reduce the amount of income subject to the 25% tax bracket in later years. Of course, the actual tax brackets will depend on your specific circumstances.

In addition to ordinary income, we can also have a tax equilibrium for our capital gains tax. Keep in mind that long-term capital gains have effectively four tax brackets: 0%, 15%, 18.8% and 23.8%. These brackets include the 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) that applies to the upper portion of the 15% tax bracket and all of the 20% bracket.

But how do we find our tax equilibrium? Knowing our taxable income and tax brackets in the current year is straightforward. Projecting those brackets decades into the future is another matter. We’ll certainly need to make several assumptions, including future tax rates, portfolio returns (which affect RMDs as higher returns result in higher tIRA balances), our asset allocation in tIRA accounts (which also can affect balances when RMDs begin), the timing of RMDs (which can change with new legislation), and charitable giving plans (which can reduce RMDs).

Even with assumptions on all of these and perhaps other factors, using a retirement planning tool is all but required. Because of charts like the ones above, my preferred tool is New Retirement. There are, however, other tools that can help, which I’ll discuss in just a moment.

Once we’ve estimated our tax equilibrium, there are several strategies we can deploy to shift taxable income from higher tax years later in retirement to lower tax years early in retirement.

Tax-Free Harvesting

In some cases retirees can take advantage of 0% on ordinary income, capital gains, or both. With ordinary income, it occurs when deductions exceed taxable income. In these circumstances, traditional retirement account distributions or Roth conversions can take advantage of the zero bracket.

With capital gains tax, the 0% bracket is even richer. In 2024, a married couple filing a joint return can enjoy 0% long-term capital gains rates up to $94,050. Keep in mind, however, that ordinary income will push into this 0% bracket. In other words, $10,000 of taxable ordinary income, after all deductions have been account for, would reduce the amount of capital gains that could benefit from 0% rates from $94,050 to $84,050.

Yet as we’ll see below, there are also strategies to take advantage of distributions from taxable accounts at the 0% capital gain rate. But there is a fundamental difference between managing capital gains tax and managing ordinary income tax generated from traditional retirement accounts. Retirees with a traditional IRA must plan for the tax impact of RMDs. Taxable accounts, from which spring capital gains (hopefully), have no RMD requirement.

Furthermore, taxable accounts we leave to loved ones enjoy a step-up in tax basis. The point is that while it may be prudent to take advantage of 0% capital gains tax in years when our taxable income permits, we should never forget that the clock is running on our time before RMDs begin.

Our Toolbox

As we move from theory to practice, it’s helpful to understand what tools we have at our disposal.

Traditional IRA Distributions: Taking distributions from tIRAs will increase our ordinary income to take advantage of relatively lower tax brackets. These distributions reduce our future RMDs, which otherwise might be subject to higher taxes. We should be mindful of possible increases in taxes on Social Security benefits, the effects on our Medicare premium, and the impact on long-term capital gains tax. We should also be mindful of ACA credits, if they are part of our plan before Medicare.

Roth Distributions: While conventional wisdom says to spend Roth accounts last, there can be good reasons to tap Roth accounts earlier, thereby decreasing our taxable income in one or more years. The lower taxable income can help us avoid additional tax on Social Security benefits, reduce our Medicare premiums, keep us in the 0% capital gains tax bracket, or protect our ACA credits. Roth distributions can also be useful if we anticipate that our heirs will be in higher tax brackets than we are or will be.

Taxable Distributions: Taking taxable distributions can benefit from 0% capital gains tax in many circumstances. They may also avoid incurring additional taxable ordinary income, assuming long-term capital gains apply. And for investments with high tax basis, much of the withdrawal may not be subject to taxation at all.

Roth Conversions: Roth conversions are an ideal way to fill up low tax brackets in early retirement while keeping as much money as possible in tax-advantaged accounts. Here one should consider the tax consequences of paying the tax on the conversion out of taxable funds. As well see in a moment, however, in some cases the benefit of taking Roth conversions instead of taking tIRA distributions may be modest.

HSA Distributions: To reduce taxes and pay for qualified medical bills, distributions from HSA accounts are ideal.

Delaying Social Security Benefits: As one delves deeper into tax-efficient withdrawal strategies, the benefits of delaying Social Security become more apparent. Once benefits begin, one must always consider the effects of the withdrawal strategy on the taxation of these benefits. Before Social Security begins, retirees have more flexibility in the strategies they choose to draw down their accounts.

Heirs’ Tax Situation: If leaving money to loved ones is important to you, another tool is to consider their likely marginal tax brackets at the time of inheritance. For example, if their tax rate is significantly higher than yours, it may make sense to spend traditional IRAs, leaving tax-free Roth accounts to them. If their tax rate is lower, the opposite approach may be ideal.

Large Medical Expenses: It may be wise to keep some tax-deferred assets available for later in retirement. Large medical expenses can be deductible, thus lowering your tax liability.

As we’ll see, in many years we use more than one tool from our toolbox. For example, we might take distributions from a tIRA to fill up the 10% tax bracket, and then take taxable distributions to take advantage of the 0% capital gains tax rate.

Strategies

So we have the theory and know the tools we can use, now let’s look at some specific strategies we can follow.

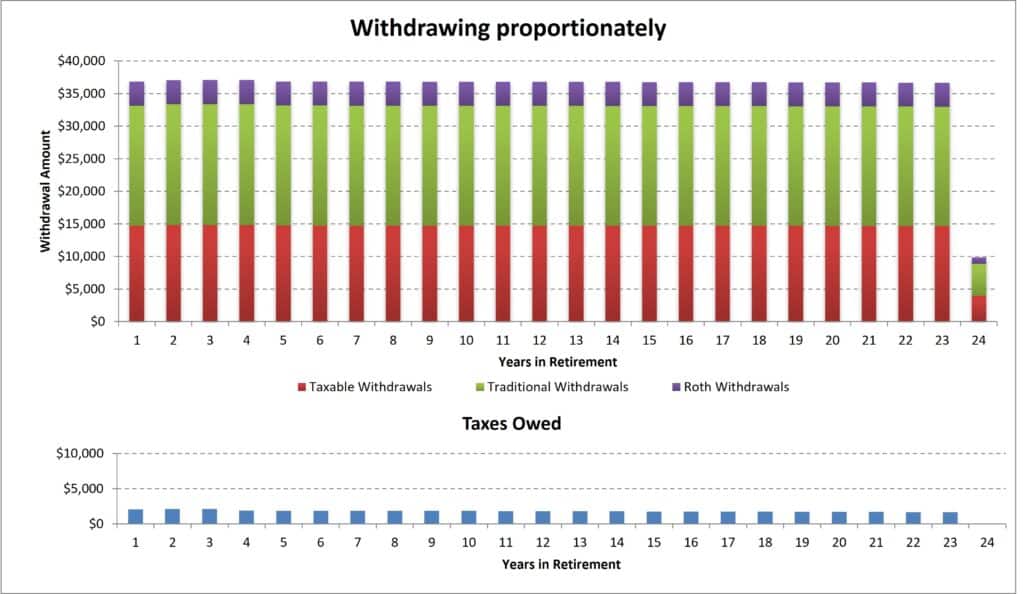

Draw Down Taxable, Traditional, and Roth Retirement Accounts Proportionally

Recall that with the rule of thumb, we draw down all of our taxable accounts before moving to retirement accounts. One alternative is to draw down account types at the same time in proportion to their balances. With this strategy, we’d take distributions from taxable, traditional and Roth accounts at the same time.

Fidelity recommends this approach in what it calls tax-savvy withdrawals in retirement. In the example used by Fidelity, the proportional approach reduced the taxes paid by 40% and extended the time the retiree’s money lasted by almost 5%.

The benefit of this approach is its simplicity. It’s easy to understand and follow. The downside is that it exhausts retirement accounts, particularly Roth accounts, too early. It also doesn’t allow us the flexibility to deal with the stealth taxes (tax on Social Security, IRMAA, ACA credits, etc.). And this approach is unlikely to be optimal.

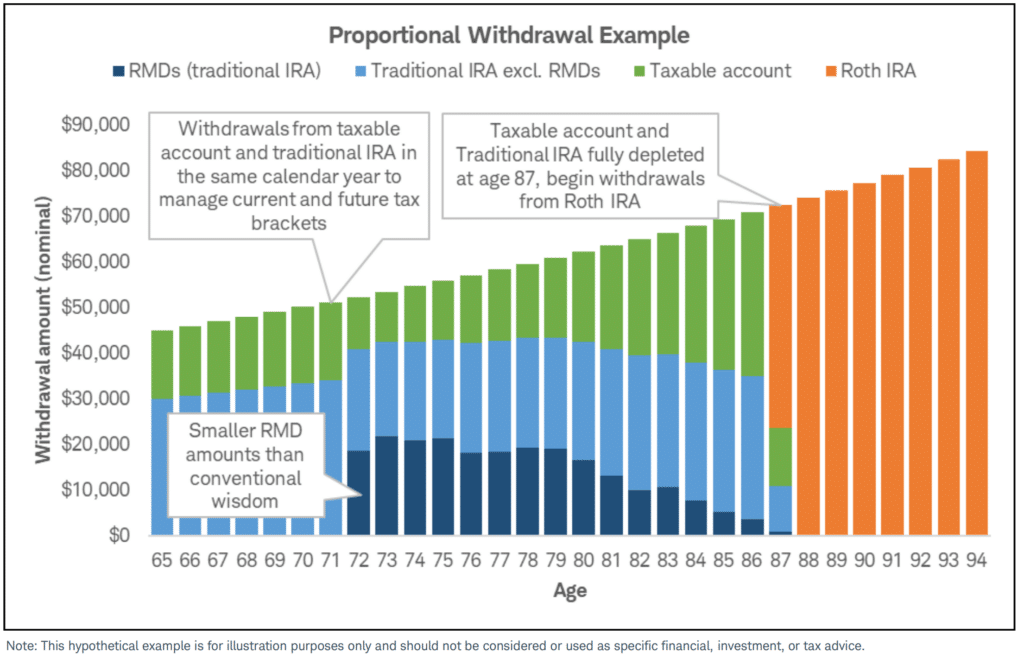

Draw Down Taxable and Traditional Proportionally, and Then Roth

An alternative is to spend down taxable and traditional accounts proportional to their balances, saving Roth accounts until later in retirement. Schwab recommended this approach, among others, in a 2022 paper.

The above graph from Schwab’s paper underscores the problem. The orange bars represent tax-free Roth distributions, where a retiree would pay no income or capital gains taxes. These years represent missed opportunities. A retiree could lower taxes in earlier years, reducing their marginal tax rates, and smoothing their taxes through retirement.

Tax Bracket Targeted Strategy

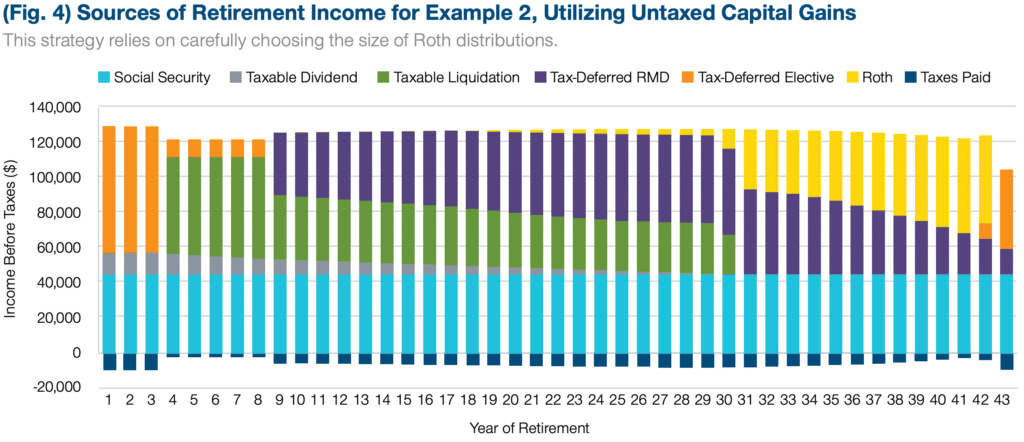

Finally, targeting a tax bracket while considering stealth taxes can lead to optimal results. One of the best papers on this strategy is by T. Rowe Price, and it is called How to Make Retirement Account Withdrawals Work Best for You. The paper compares the rule of thumb to a tax bracket-targeted strategy that also considers stealth taxes. It shows examples of three different levels of income and wealth.

As an example, here’s the optimal withdrawal order strategy for a couple with $2 million in assets, 40% of which are in taxable accounts:

This optimized approach increased portfolio longevity by 2% and estate value at age 95 by 6%. The key takeaway: “Retirees who can’t take advantage of the 0% bracket may still be in a position to generate cash flow from taxable accounts without paying capital gains taxes.”

The question remains: how can we undertake this analysis for our specific set of circumstances? As you see below, several available tools have withdrawal order optimization as a feature. These tools, however, optimize under the assumption that a retiree will withdraw from one account type at a time.

While New Retirement lacks an automated optimization tool, it enables you to create your own year-by-year. The starting point is to create your retirement plan in New Retirement using the default rule of thumb. This will give you a picture of your tax brackets and liability throughout retirement. From there, you can begin to manually change the order of withdrawals and/or add Roth conversions to smooth out your tax liability.

I walk through how to do this in the following video:

Roth Conversions vs Traditional IRA Distributions

When filling low tax brackets, many retirees can choose between converting tIRA to a Roth IRA or simply taking tIRA distributions. When evaluating this choice, I assumed that the Roth Conversion strategy would always be the clear winner. Conversions enable retirees to keep money in tax-advantaged accounts longer.

It turns out, however, that in some cases the advantage is modest. In both cases the retiree is taking advantage of the lower tax brackets, often in early retirement. If their taxable account is invested in a tax-efficient way, the Roth Conversion strategy may have modest benefits over tIRA distributions, particularly at lower income levels:

In the scenarios we evaluated (including many not discussed in this paper), Roth conversions were sometimes beneficial, but not overwhelmingly so. At lower income levels, the potential benefit of a conversion at a low tax rate is largely negated by higher taxation of Social Security benefits. (See discussion of the “tax torpedo” in Appendix 1.)

How to Make Retirement Account Withdrawals Work Best for You

Conversions may be more beneficial at higher income levels (e.g., reducing unneeded RMDs taxed at 24% via Roth

conversions taxed at 12%). To a lesser extent, the modest benefit of a Roth conversion reflects the fact that we assume a relatively tax-efficient taxable account.

As pointed out by Michael Kitces in a 2016 article, however, the Roth Conversion strategy under certain circumstances can result in higher after-tax wealth. But one shouldn’t assume that the benefit is worth the extra effort of undertaking the conversion and funding the tax payments.

There are other considerations, too. Roth conversions give retirees tax diversification they may be able to use in later years to control, to some extent, their taxable income. At the same time, conversions require sufficient assets in taxable accounts to meet both spending needs and the additional tax liability.

Tools

The following tools can assist in determining an optimal ordering strategy.

Research

The following articles for my database are related to retirement account drawdown order.