How Much Cash Should Retirees Keep On Hand?

Some of the links in this article may be affiliate links, meaning at no cost to you I earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase or open an account. I only recommend products or services that I (1) believe in and (2) would recommend to my mom. Advertisers have had no control, influence, or input on this article, and they never will.

Moving from a regular paycheck to living off of your nest egg is not an easy transition. At least it hasn’t been for me. One of the many decisions retirees must make is how much cash should they have in the bank.

For some it’s a question of budgeting. They keep enough to pay the bills over the next several months, but that’s it. For others cash acts as a buffer in the event the stock market drops 10%, 20% or more. For those who see cash as a buffer, several more questions need to be considered:

- How much cash should you keep in the bank?

- How do you decide when to replenish your spending account?

- Do you factor the amount of cash you have into your overall asset allocation?

In this article I’ll explore these questions. We’ll look at some research papers that address these questions. We’ll also talk about how you can get the psychological benefits of holding lots of cash without actually holding lots of cash.

The starting for all of this is the 4% Rule. First, however, we need to cover the basics.

Featured Offer: Ponce Bank 5-Month No Penalty CD

What is Cash?

For our purposes, I define cash as money in an FDIC-insured account (checking, savings, money market account or possibly a certificate of deposit) or a money market fund. The later is not FDIC-insured, but it’s extremely safe. U.S. government T-bills would also qualify as cash.

What I don’t include in cash are bonds with durations of longer than one year.

What about Social Security, Pensions, Annuities, and Part-Time Work?

Retirees fund retirement from many sources. Most receive social security. Many have pensions or annuities. And some, myself included, still do part-time work to generate some income. All of these sources generate cash for us, typically on a monthly basis.

The question we are addressing is how much cash, over and above any cash these other sources generate, do we need to pull from our investments. In other words, how much do we need to pull from 401k, IRA and taxable accounts each month or year for living expenses.

These other sources will of course reduce how much we have to pull from our investments. But most of us have to pull something out, and that’s what this article addresses.

The Budget-Dividend Strategy (My Preferred Approach)

My preferred approach to cash in retirement is what I call the Budget-Dividend Strategy. The nice thing about this approach is that it addresses three liquidity concerns at the same time:

- It guarantees that I’ll always have cash on hand

- It helps with budgeting

- And it coincides with quarterly dividend payments, which can be used as a source of funds

Here’s how the Budget-Dividend Strategy works.

At the start of the year I pull six months worth of living expenses from our investment accounts. In our case the money gets deposited into our checking account.

When the balance declines to three months of living expenses, we add cash to bring the balance back to the six months of expenses level. If we are generally on track with our budget, this should happen after three months.

The timing is convenient because ETFs and mutual funds typically pay dividends at the end of each quarter. In our taxable account, we do not automatically reinvest dividends. So once the dividends hit our money market fund in our brokerage account, I can move some or all of them over to our bank account.

If we need more than the dividends give us, I withdrawal additional funds from investment accounts. Here I make the decision on a number of factors, such as taxes and which asset classes have performed best.

Once we start taking Required Minimum Distributions (still two decades away), we’ll use the RMD to fund living expenses as well.

Benefits of the Budget-Dividend Strategy

The are several benefits to this approach.

First, we keep the vast majority of our capital fully invested. Even assuming an initial 4% distribution per year, we never have more than 2% in cash (6 months of living expenses). And this number drops to 1% (3 months of living expenses) before we replenish the cash account.

Second, the timing of when we replenish the account coincides with distributions from ETFs and mutual funds. This isn’t necessary, and may be irrelevant for those without significant taxable investments. But it’s convenient for us.

Third, the approach also makes budgeting easier. We track our spending in Personal Capital and Tiller Money. This approach to cash, however, makes it easy to know at a glance if we are on track, over spending or under spending.

The No Cash Strategy

One approach to cash in retirement is virtually no cash at all. One could sell investments monthly to cover just one month of expenses. If most spending is put on a credit card, the no cash strategy could work.

Personally, I find the idea of tapping my investments monthly to be too much of nuisance. Still, it’s worth pointing out that one could take this approach. For those who do, finding a broker that offers check writing, online bill pay, and perhaps even a debit card would be useful. Even here, however, you’d be transferring funds from stock and bond funds to a money market fund every 30 days, which many would find tiresome.

The Buffer Strategy

Our approach to cash keeps the vast majority of our assets fully invested. Some advocate a different approach called the Buffer Strategy. The idea is to keep as much as five years worth of living expenses in cash. The strategy has some initial appeal.

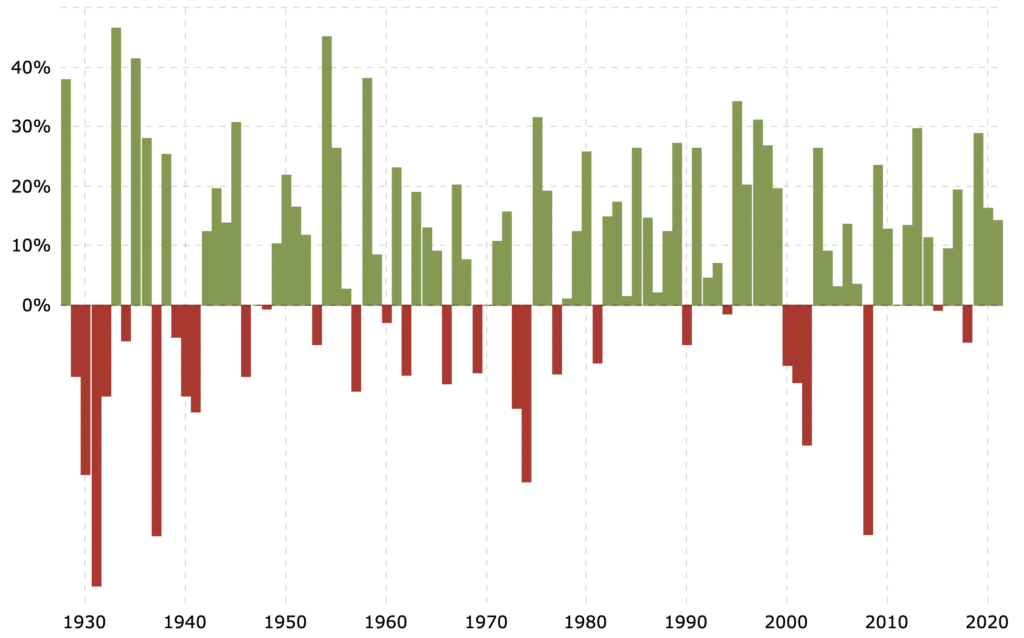

Over the past 100 years, the worst stock market performance saw a decline four years in a row (from 1929 to 1932). The market has never been down five years in a row.

Here’s a chart of the S&P 500’s yearly performance dating back to 1928:

Of course the market could be down 5 years in a row sometime in the future. But the idea of a cash cushion is to avoid selling stocks when the market is down. It has some intuitive appeal.

And it’s a bad strategy.

First, if we rebalance our portfolio at least once a year, we won’t sell stocks in a bear market. When the market is down significantly, the simple act of rebalancing will cause us to sell bonds and buy stocks. This is true even if bonds decline a bit.

For example, in 1931 the 10-year Treasury Bond was down 2.56%. The S&P 500 (or equivalent) was down more than 43%! In that scenario, we still be selling bonds to buy stocks as part of rebalancing.

Just as important, holding five years worth of cash creates a serious drag on our portfolio’s performance. Let’s make sure we understand why.

Cash and the 4% Rule

The 4% Rule comes from a 1994 paper written by financial planner Bill Bengen. Using historical returns and inflation data, Bengen tried to answer how much a retiree could spend each year without going broke.

His conclusion was that a retiree could spend 4% of his or her nest egg in the first year of retirement. Thereafter, they could increase this amount by the rate of inflation (he used CPI). Following this approach, he concluded, a retiree’s nest egg would last at least 30 years, and in some cases 50 years or longer.

There were, however, some important underlying assumptions in his work. For example, he assumed retirees invested in an S&P 500 index fund for stocks and an intermediate U.S. government bond fund for bonds. He also concluded that stocks should represent 50 to 75% of a retiree’s asset allocation. Any more and a big stock market decline (e.g., 1929 to 1932) would shorten the longevity of a portfolio. Any less and a return to double-digit inflation could do irreparable harm.

So what does this have to do with how much cash we should hold?

For his analysis, Bengen assumed that retiree withdrew funds from the portfolio once a year and then rebalanced. The rebalancing did not factor in the cash that was just taken from the portfolio. His focus was not on how much cash to hold. That’s just the approach he chose for his analysis.

Nevertheless, it’s important to keep his approach in mind. For those choosing to deviate from a once-a-year distribution strategy (at most) to hold significantly more cash, keep in mind that the conclusions from his research may not hold. And indeed, subsequent research confirms this outcome.

Research on the Buffer Strategy

Arguably the most comprehensive study comes from Professor Walter Woerheide, Ph.D., ChFC, CFP®. At the time of publication, he was the Frank M. Engle Distinguished Chair in Economic Security Research, at The American College in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania.

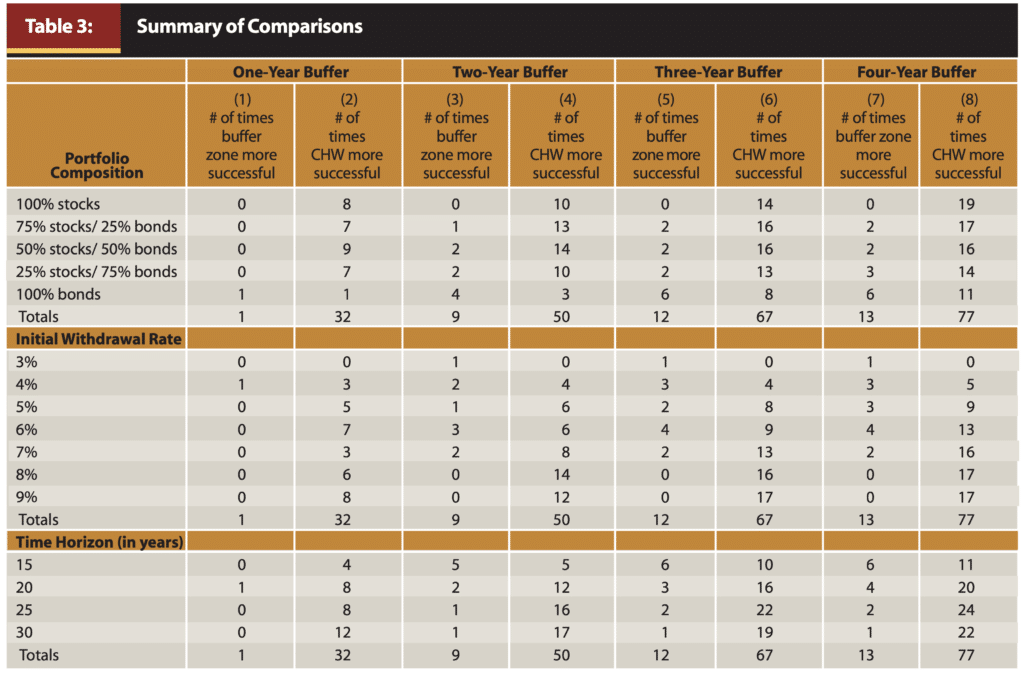

In 2012 Professor Woerheide published a paper entitled, Sustainable Withdrawal rates: The Historical Evidence on Buffer Zone Strategies. He evaluated cash buffers of one to four years, using a replenishing strategy based on whether the investment portfolio was up or down the previous years.

If the investments were up, the cash buffer was replenished along with any required withdrawals. If the portfolio was down, withdrawals came from the cash buffer. The only time cash came from the investment portfolio following a down market was if the cash buffer were exhausted.

Looking at several different asset allocations, the results were clear. A cash buffer strategy underperforms a standard rebalancing approach. It reduces the likelihood that a portfolio will last 30 years. It also reduces the portfolio’s balance at death.

Here’s a summary of his findings:

Several other studies have confirmed these results:

- Cash reserve buffers, withdrawal rates and old wives’ fables for retirement portfolios

- Research Reveals Cash Reserve Strategies Don’t Work… Unless You’re A Good Market Timer?

- Cash Buffers, Sustainable Withdrawal and Bear Markets

Harold Evensky

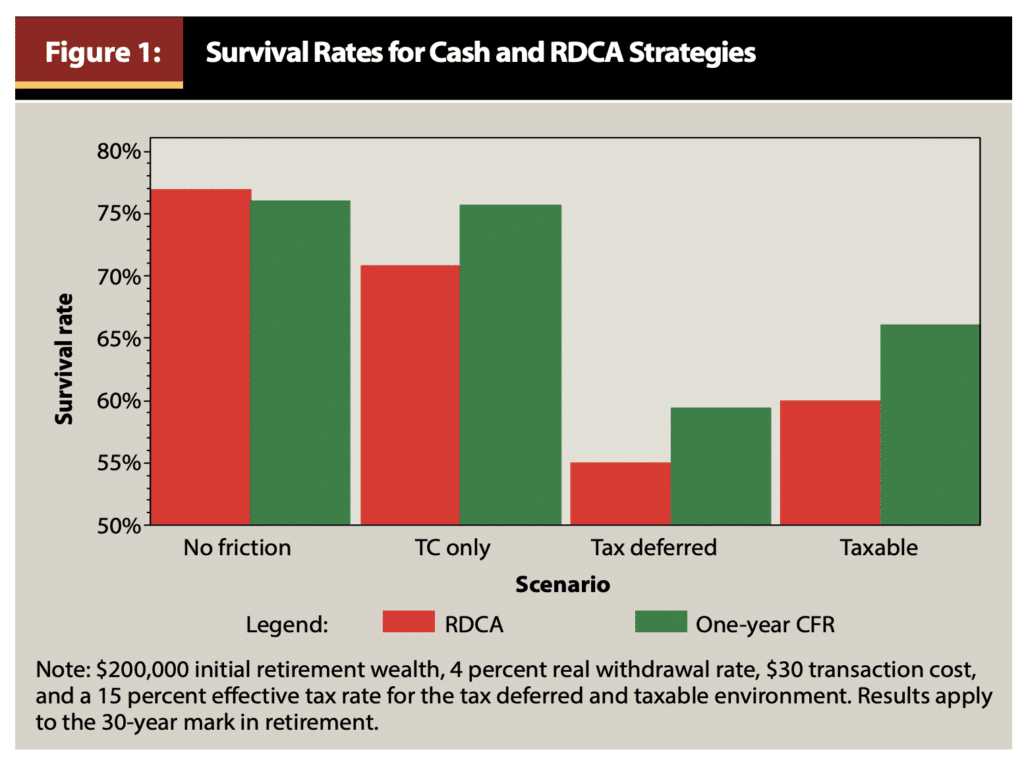

Harold Evensky is the father of the bucket strategy. He’s also a proponent of the Buffer Strategy for cash. In 2021 he co-authored a paper (The Benefits of a Cash Reserve Strategy in Retirement Distribution Planning) that concluded a cash buffer equal to one year of expenses actually improved the likelihood that a portfolio could be sustained for at least 30 years. His study is the outlier and deserves a brief comment.

He found the a 1-year buffer strategy (he called it the Cash Flow Reserve or CFR) out performed a standard rebalancing approach (RDCA–Reverse Dollar Cost Averaging), particularly with taxes and transaction costs were factored in. Here’s a summary of his findings:

There are several serious flaws in the study.

First, it used a 1-year cash buffer that was allowed to fall to just two months. As a practical matter, that’s no cash buffer at all.

Second, he used a Monte Carlo simulations instead of historical data. In and of itself this isn’t a problem, but the inputs he used heavily favored cash. He assumed an average stock return of 8.75%, well below the historical average. He also assumed a 3.5% return on cash with a 3.0% rate of inflation. This gave cash a 0.50% real return.

In other words, the study was designed to reach a certain conclusion, in my opinion. The fact is that a significant cash cushion represents a significant drag on performance that hurts retirees in the long run.

How to Sleep at Night with Little Cash in the Bank

While it’s clear that the Buffer Strategy underperforms, we need to address the psychology factors. As someone who is semi-retired, I understand firsthand the fear of spending investments. That fear grows when the stock market drops as it did at the start of the Covid pandemic.

To address this real concern, here are a few approaches retirees can take that won’t do as much harm as holding too much cash.

First, calculate how long you can live on just your bonds. If you have a 60/40 stock/bonds allocation, for example, you can live on just the bonds for about 10 years, assuming an initial 4% withdrawal.

This approach assumes your bonds are primarily U.S. government short and intermediate-term bonds. Riskier bonds, such as high-yield or emerging market debt might not provide as much comfort. The point is that recolonizing just how long your bond portfolio can get you may help you weather a stock market decline.

Second, and related to the first, is to allocate some of your bonds to cash. For most this would mean a money market fund. For example, a 60/40 portfolio would become a 60/30/10 portfolio (stocks/bonds/cash). Studies have found that converting some of the bonds to cash doesn’t have a major effect on the longevity of the portfolio.

Bill Bengen actually reached this conclusion in a 1997 paper. He found that a 10% allocation to short-term U.S. Treasury Bills did not significantly reduce the starting safe withdrawal rate of about 4%. Others have reached similar conclusions (see here and here).

Final Thoughts

Investing during retirement can be stressful. Still, we need to resist the urge to play it “safe” by holding too much cash. What may feel safe could over time do far more harm than good. A simple approach of three to six months in cash keeps are capital invested while still giving us ample room to do with unexpected expenses.

Rob Berger is a former securities lawyer and founding editor of Forbes Money Advisor. He is the author of Retire Before Mom and Dad and the host of the Financial Freedom Show.