Higher Isn’t Always Better: The Surprising Truth About Safe Withdrawal Rates

Some of the links in this article may be affiliate links, meaning at no cost to you I earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase or open an account. I only recommend products or services that I (1) believe in and (2) would recommend to my mom. Advertisers have had no control, influence, or input on this article, and they never will.

Morningstar recently released its annual report on the state of retirement income. It’s the fourth such annual report. In each, Morningstar uses assumptions about future market returns and inflation to estimate the safe withdrawal rate (SWR).

In this year’s report, Morningstar estimates that the SWR is 3.7%. This means that one could spend 3.7% of their savings in the first year of retirement. Thereafter, they could increase their spending annually by the rate of inflation. In doing so, they would have a 90% chance of not running out of money during a 30-year retirement.

Last year, Morningstar estimated that the SWR was 4.0%. The year before that 3.8%. The year before that 3.3%.

All of this raises two important questions:

- Why does Morningstar’s SWR projection keep changing?

- Is a higher SWR better?

The second question seems silly. Of course a higher SWR is better, right? Well, not necessarily. But let’s start with the first question.

Why SWRs Change

The SWR for any given year is a function of a number of assumptions. For example, to calculate the annual SWR for a given year, we need to decide on the following:

- The length of retirement (e.g., 30 years)

- The asset allocation (e.g., 50% stocks, 50% bonds)

- The assets that make up the stock and bond allocations (e.g., S&P 500 for stocks, intermediate U.S. Treasuries for bonds)

- How we will measure inflation (e.g., Consumer Price Index)

- How we will rebalance our portfolio (e.g., once a year)

- The Chance of Success required (e.g., 100%, which Bill Bengen used in his 1994 paper; 90%, which Morningstar uses in its annual series on the State of Retirement Income)

As any of the above items change, the SWR also changes. As such, for any given year there is not one single SWR. There are millions of them. Once we settle on the assumptions we’ll use in our calculations, our work has just begun.

Now we need data. We need returns data for the investments we’ve chosen to make up our portfolio. We also need the annual inflation rate for whatever inflation metric we’ve chosen. And we need this data for however long we’ve chosen for retirement, often 30-years in academic papers. That, in turn, means that we can only calculate SWRs for retirements that began at least 30 years ago, assuming we are using historical data (rather than projections as Morningstar does).

As we make these calculations, we quickly learn that the SWR changes from year to year. It also changes from month to month when we look at retirements beginning each month of the year, rather than focusing just on January 1st of each year.

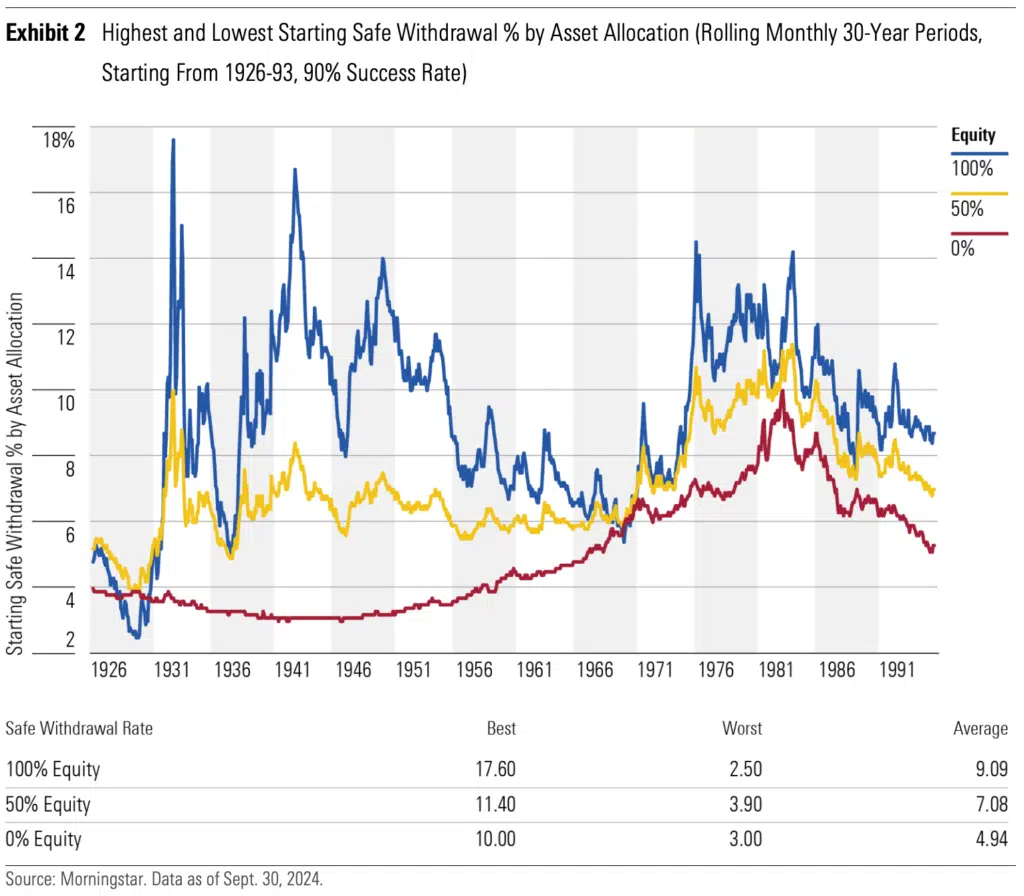

In its report, Morningstar includes this chart of historical SWRs based on three different asset allocations:

Change is the norm. And the SWRs can change dramatically in a short period of time.

For example, the above chart shows that with a 100% stock portfolio, the lowest SWR was in mid-1929 at just 2.5%. Three years later in July 1932, the SWR skyrocketed to 17.6%.

Why do SWRs change from month to month and year to year? They change based on the starting point for retirement because future returns and inflation change. Pick any two consecutive years or even months and measure returns and inflation for 30 years, and you’ll get different results. And these results can be dramatically different even over relatively short periods of time, as noted above.

In the case of 1929 vs. 1932, stock prices plummeted nearly 90% in just three years. Those who retired in 1929 walked right into a buzzsaw. Those who waited until 1932 avoided the market crash.

Here you may be thinking, “but didn’t the 1932 retiree have a lot less money saved than they did in 1929 before the crash?” Great question, which leads to the second part of this article.

Before we get there, however, we need to look at what is known as sequence of returns risk.

Sequence of Returns Risk

Not all years in retirement are created equal. Investment returns and inflation don’t matter much in year 30 of retirement, if we assume death comes knocking at the end of that year.

In contrast, returns and inflation matter a lot during the first 10 years of retirement. They set the stage for what comes next. High inflation in the first decade of retirement haunts us for the last two decades, even if inflation comes back down. Those high prices in the first 10 years get baked into everything we buy forever, unless we experience significant deflation (which generally hasn’t happened in the U.S. over the last 100+ years).

Likewise, a crushing stock market in the early years of retirement can drain our savings. In extreme cases, we may run out of money before we can enjoy sunnier days in the market down the road.

Combine high inflation and bad stock market years in the first decade of retirement and we have a perfect storm. That’s exactly what happened to those retiring in the later half of the 1960s. The high inflation of the 1970s and early 1980s, combined with some serious stock market crashes, led to very low SWRs.

This risk of bad times in early retirement is known as the sequence of return risk. It’s a mouthful, but the idea is that the order of returns and inflation matter during retirement, not just the 30-year averages.

Now back to our regularly schedule program.

Why a Lower SWR Is Often Better (Or At Least Not Much Worse) Than a Higher SWR

Recall that a 100% portfolio had a SWR of 2.% in 1929 and 17.6% in 1932, according to Morningstar. Question: What happened in the stock market in the three years leading up to these dates?

Let’s start in 1929. In the three prior years, U.S. stocks were up 11.62%, 37.49% and 43.61%.

Source: Slickcharts

So while a 2.5% SWR in 1929 is low, it gets applied to retirement savings that enjoyed substantial growth in the previous three years.

What about the 17.60% SWR of 1932? In the three previous years, stocks returned -8.42%, -24.90% and -43.34%. It was ugly!

We can dial in even more. Recall that the 17.60% SWR is for those who retired in July 1932. What happened in the first half of that year? More ugliness.

In March, April and May of 1932, stocks returned -12.5%, -18.8% and -22.1%. And to be clear, those are monthly returns. (Source) Yikes!

And guess when stocks hit rock bottom following the 1929 crash. Yep, July 1932. To be specific, stocks hit bottom on July 8, 1932. By then stocks had fallen nearly 90%.

So on the one hand, retirees in July 1932 would go on to enjoy a 17.6% SWR. Of course, they probably weren’t celebrating. Their portfolios had been ravaged. Who in their right mind would pull out 17.6% of their retirement savings for year one of their retirement at that time?

Then again, stocks were up 31.1% and 37.3% in July and August of 1932 (yes, monthly returns!), so who knows?

The point is that extremely low SWRs typically follow bull markets, where retirement savings are at or near an all time high. Extremely high SWRs typically follow bear markets, where retirement savings have been slashed.

There are of course other considerations. Inflation is the silent killer of retirement savings. Just ask anybody who retired in the late 1960s. The stock market returns in the 1970s weren’t terrible, although 1973 and 1974 were not fun. But it was double-digit inflation through 1982 that really hurt retirees.

A retiree’s asset allocation also matters. The above assumed a 100% stock portfolio, something most retirees would never consider. Still, the underlying idea is the same. High SWRs usually get multiplied against smaller retirement account balances, while lower SWRs go with higher retirement balances.

What About Now?

Go back up to the chart showing the S&P 500 annual returns. Beginning in 2009, with the exception of two years, stocks have been going up and up. Today they are at extremely high valuations. Retirement portfolios have grown to their highest levels.

History tells us what’s next. Bull markets are followed by bear markets. Stock returns revert to the mean. Trees don’t grow to the sky, and neither do stock prices.

I can’t predict with confidence the actual SWR that will apply to 2025. We’ll know that in 30 years. What I can say with confidence is that it will much, much closer to Morningstar’s 3.7% prediction than it will be to the 17.6% SWR of July 1932. The good news for those retiring now is that they get to multiply that relatively low SWR against retirement savings that have enjoyed substantial growth over the past 15 years.

Rob Berger is a former securities lawyer and founding editor of Forbes Money Advisor. He is the author of Retire Before Mom and Dad and the host of the Financial Freedom Show.