How Should We Evaluate Financial Planning Fees?

We earn a commission from the offers on this page, which influences which offers are displayed and how and where the offers appear. Learn more here.

The cost of financial advice and how that cost is calculated are hotly debated topics among financial professionals and the clients they serve. The most common fee structure is based on Assets Under Management (AUM). An advisor charges a client an annual fee equal to a percentage of the amount of investments they manage for the client. A 1% AUM fee is often quoted as the industry standard, although many advisors charge much more, and a few charge less.

Recognizing the enormous costs a percentage of AUM can generate, some advisors and clients have moved away from this model. Alternatives include hourly fees, one-time flat fees, and ongoing subscription fees. The model chosen often depends on the advisor’s services.

Financial services encompasses four primary types of advice: (1) financial planning, (2) tax planning, (3) estate planning, and (4) investment management. While these can be discreet services (e.g., having an attorney draft a will or an advisor preparing a one-time financial plan), there is often overlap. For example, financial planning might include when to claim social security, yet that decision can have implications for both tax and investing.

All of this raises two important questions for clients:

- How should we think about the appropriate fee structure?

- What is a reasonable fee?

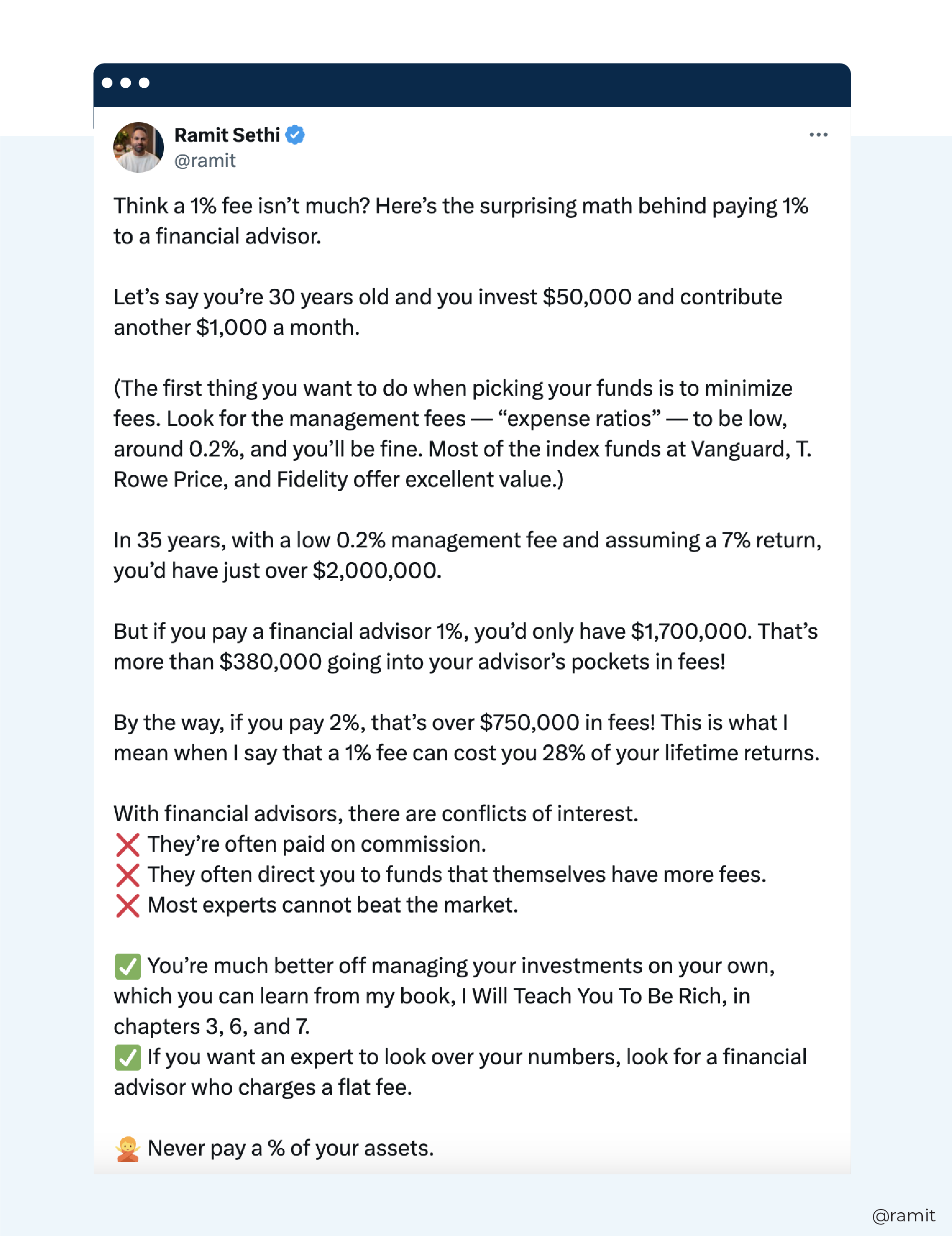

Recently, Derek Tharp, Ph.D., CFP, CLU, RICP published an article on Kitces.com that attempted to quantify the “real” impact on a financial advisor’s clients’ nest egg. The article was prompted by a tweet by financial influencer Ramit Sethi. Here’s the tweet:

The math that Ramit walked through is well-trodden ground. I’ve done the same math many times to show people the power of compounding and why you don’t want to let anything stand in its way. Even tools, such as Empower, offer free calculators showing the devastating impact investment fees can have on our lives.

So what’s the problem? Well, Mr. Tharp offered three objections to Ramit’s calculations that are worth considering. Here they are:

- It’s unfair to compound the cost of an advisor’s AUM fee over time. We don’t do that with other types of expenses we incur, so we shouldn’t do it with investment fees.

- The calculation does’t take into account the value the client received or the increased wealth they enjoyed based on that advice (e.g., tax advice that saves them money, investing advice that keeps them in the market when stocks are down).

- Subscription based fees can be as expensive and even more costly than AUM fees.

Let’s examine each of these objections.

Compounding AUM Fees

When I go to the store to buy groceries, I don’t calculate how much money I’d have 30 years from now if instead of eating this week I invested the money. Why then, Mr. Tharp argues, should we compound AUM fees when evaluating their effect on our wealth?

There are several good reasons.

First, understanding the lost compounding opportunities of money we spend can help us see the long-term consequences of our daily decisions. For example, if somebody who spends $500 a month on 12 different streaming services came to me for budgeting help, I would absolutely show them how much they could have ten or twenty years later if they saved and invested some of this.

The same is true when deciding how much to spend on a house or car. It allows us to take the here and now and translate it into the future. And it helps us decide what is important to us, not just based on today, but also in the years to come.

We won’t do this with every expense, of course. New parents going to the store to buy diapers (an example Mr. Tharp used) probably don’t break out a spreadsheet to calculate how much more wealth they could have 40 years hence if they didn’t spend the money. (Although maybe they did just that nine months ago.) The same is true for just about any basic need.

Thus, we can and should understand the lost opportunity cost of some of the money we spend on discretionary items, but probably not money spent on necessities. Even with discretionary spending, I wouldn’t calculate the lost compounding every time. When my son and I go to the movies, I’m not breaking out a calculator to compound the cost of a ticket.

It is, however, a very helpful approach to large discretionary expenses and ongoing discretionary expenses. Investment fees fall into both categories.

When it comes to AUM fees, they may not seem like much today. One percent doesn’t seem that bad. It’s only when we see the long-term effects of the fee on our wealth that we can make an informed decision as to whether the services we receive today are worth the cost. And these expenses are discretionary.

By that I don’t mean that hiring a financial advisor is discretionary, although for many people it is. For some, however, getting financial help is closer to a necessity. What is always discretionary is whether you agree to an AUM fee structure. Before you do, understand how the cost will affect your wealth over time.

Second, AUM fees have a direct affect on the compounding of money we’ve already saved. Should we work hard to spend less than we make to save even more? Of course. But these fees hit money we’ve already worked hard to save. Our goal with this money should be to compound it as much as we can given the risk we are willing to take.

As Charlie Munger put it, “The first rule of compounding is to never interrupt it unnecessarily.” AUM fees interrupt compounding each and every year, and it’s appropriate to understand how this interruption will affect our wealth over time.

Third, ongoing AUM fees are unique among other types of expenses in two ways. They come directly out of a client’s investment account automatically, and they rise as a client’s portfolio rises. Both of these are critical to the business of AUM advisors. The result is that clients don’t feel the effects of these fees, even as they go up most years.

By seeing the effect these fees will have on future wealth, it helps clients internalize these fees. This in turn empowers clients to assess for themselves whether the services they are receiving are worth the long-term cost of the fees.

Value

The second objection Mr. Tharp has is that Ramit doesn’t account for the value an AUM advisor brings to their clients. This objection is easy to address. He’s right, but he misses the point.

He’s right that Ramit doesn’t discuss the value. He’s also right that the value can be substantial. Advisors can help clients avoid making investing mistakes during volatile markets. They can provide valuable tax and financial planning. They can also provide peace of mind.

But he misses the point. All of the above can be paid for without sacrificing a percentage of your investments in an AUM model. The value one receives from the advice doesn’t justify an AUM fee structure. Further, the AUM fee structure often incentivizes advisors to recommend expensive, complicated portfolios that provide the advisor job security, but aren’t in the best interest of their clients (more on that in a moment).

Subscriptions

Mr. Tharp noted that Ramit endorses Facet Wealth for a fee. Facet Wealth is a flat-fee based advisor. Its fees currently range from $2,000 to $6,000 a year. Based on this, Mr. Tharp evaluated the impact these fees would have on somebody who, beginning in 1986, began saving for retirement with Facet Wealth using either the $2,000 fee level or the $6,000 fee level, all numbers adjusted for inflation.

The results were as interesting as they were misleading. First, he noted that with Ramit’s AUM fee calculations, a client lost 25% of their nest egg over 40 years. Using the $2,000 fee level, the client would have lost 23%, according to Mr. Tharp’s calculations. And with the $6,000 fee level, they would have lost a whopping $70%.

So why is this misleading? The hypothetical client started with a very small nest egg, as most of us do. Under those circumstances, a flat-fee advisor generally doesn’t make any sense. The costs translate into a percentage of the portfolio much higher than even AUM advisors. In contrast, an AUM advisor in those early years would make all kinds of sense given the low costs. Of course, many advisors wouldn’t accept such a client due to minimum asset requirements or would set a minimum fee, something Mr. Tharp doesn’t address.

Mr. Kitces’ firm, Buckingham Wealth Advisors, charges a minimum fee of $3,000 for wealth management services. Such a fee would make little sense for someone with say $25,000 to invest. Its AUM is up to 1.25%, according to its ADV. I didn’t see a minimum for Mr. Tharp’s firm, Conscious Capital, although its AUM fee goes up to 2.00%, according to its ADV.

Had Mr. Tharp evaluated a retiree looking to move a $1,000,000 401(k) to an IRA, the results would have been very different. One doesn’t need to do much math to know that a 1% AUM advisor’s fee of $10,000 a year (1% of $1 million) would far exceed Facet Wealth’s low-tier fee of $2,000 (its $6,000 tier fee provides the same investment services as the $2,000 level fee).

As an interesting aside, if one retired in 1966 and followed the 4% rule, they would see their balances fall significantly during retirement. Under these circumstances, an AUM arrangement may prove less expensive because the portfolio’s balance declines to $0 over 30 years. As Mr. Kitces has pointed out, however, this doesn’t happen very often.

Take the assets even higher to say $2,000,000 to $10,000,000 and the differences become astronomical. And that’s true even after factoring in the lower AUM fees that most advisors offer for high net worth clients. Using some of my favorite retirement planning tools, you can see for yourself how a 1% AUM fee vs. a $2,000 flat annual fee affects retirement spending. Let’s just say that for any retiree with about $250,000 or more, the $2,000 flat fee wins much of the time.

The point isn’t to sing the praises of Facet Wealth. You can check out my review of the firm here. Rather, it’s to point out that the conclusions Mr. Tharp reached were highly specific to the assumptions he made. Those assumptions likely don’t apply to you. They certainly don’t apply to me.

Types of Financial Services

I noted at the start of this article that financial services span four broad areas of expertise: financial planning, tax planning, estate planning, and investment management. The AUM model applies to investment management, not the other three. Of course, many firms package investment management with one or more of the other service categories. They often use these other services to justify the AUM fees.

It’s important, however, to evaluate these services separately. Imagine going to an advisor for a financial plan. How would you react if they told you the fee was 1% of your investable assets for life? That doesn’t make much sense.

It doesn’t become more sensible because you wrap these services around investment management. Most of us don’t need ongoing financial planning, tax planning, and estate planning each and every year. If a major life change happens, we may need to check in with an advisor. We also may need an annual call for one or two hours. But these services don’t justify an AUM fee.

Investment Management

At the heart of AUM fees is investment management. Yet managing an investment portfolio is not rocket science. One can create a wonderful portfolio with three to five index funds that diversify your investments around the globe. Many hourly and flat-fee advisors provide these services. Given this, why would anybody pay 1% or more a year in fees?

Here we need to take a step back. Many people are intimidated by investing. They are scared their money won’t last in retirement. They are scared they will make a mistake. They just want somebody else to handle it for them. Fair enough.

In this context, a 1% fee seems more than fair. It may even seem miserly. Cash back credit cards pay more than this. The fee doesn’t come out of their checking account or show up as a charge on their credit card. They probably don’t even include it as an expense in their favorite budgeting software.

It’s this lack of practical transparency that allows 1% AUM advisors to flourish. Clients don’t feel the expense like they do with other spending. And they don’t appreciate the long-term effects of the fee. (That takes us back to compounding the fees to see their long-term effect, and why that’s so important.)

But there’s one other aspect of AUM fee structures that clients should consider that I alluded to earlier–complexity.

Many expensive AUM advisors create unnecessarily complex portfolios. I’ve seen clients with less than $1 million in portfolios with dozens and dozens of exotic ETFs, individual stocks, and other unnecessary investments. Advisors do this even though study after study after study shows us that a simple, low-cost index fund portfolio performs better.

It’s interesting that you won’t likely see these ridiculous portfolios from hourly or flat-fee advisors. I also don’t see them from AUM advisors who charge a more reasonable fee (say 0.50% or lower). These advisors tend to use a few low-cost index funds to create their portfolios. That’s what Facet Wealth does.

Move to more expensive AUM advisors, however, and you are likely to see far more complexity in the portfolio. Why? I suspect that for expensive AUM advisors, complexity means job security. A non-professional can’t be expected to understand, let alone manage, a portfolio of dozens of actively managed funds, many of them with exotic names that include terms like Alpha, Momentum, MLP, Strategy, Inverse, Alternative, Buffer, and Covered Call. Leave that to the professionals.

And it’s unlikely that these professionals will offer to compare the performance of their portfolios to a simple index fund portfolio. They might compare them in the short term, particularly in a bear market, to show clients how they saved them from some of the market downturn. But don’t expect them to do so over the long haul. The comparisons will almost always favor the low-cost index fund portfolio.

The takeaway should be that before hiring any advisor to manage your investments, get a clear understanding of how they would invest your money. And keep your fees, however they are calculated, as low as possible.

Perhaps Mr. Tharp and Mr. Kitces will show us a standard portfolio they use in their practice.

Until then, check out my list of low-cost financial advisors here. Note that I have no financial interest whatsoever with any of these advisors.