Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data

Author(s): William P. Bengen, CFP

Topics:

- Safe Withdrawal Rates

Year Published: 1994

My Rating: ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

One Sentence Summary: Using a constant dollar (inflation-adjusted) approach to retirement withdrawals, an initial 4% withdrawal followed by annual adjustments for inflation should enable the portfolio to last at least 30 years based on historical stock and bond returns and inflation.

Summary

Using a constant dollar (inflation-adjusted) approach to retirement withdrawals, an initial 4% withdrawal followed by annual adjustments for inflation should enable the portfolio to last at least 30 years based on historical U.S. stock and bond returns and U.S. inflation. The paper makes several important assumptions to reach this conclusion, including the use of the S&P 500 to represent stocks, intermediate-term Treasuries to represent bonds, and the CPI to represent inflation. In also assumes annual rebalancing, the payment of no investment fees, and a retirement that begins on January 1.

Here are some of the key findings I found the most useful or interesting:

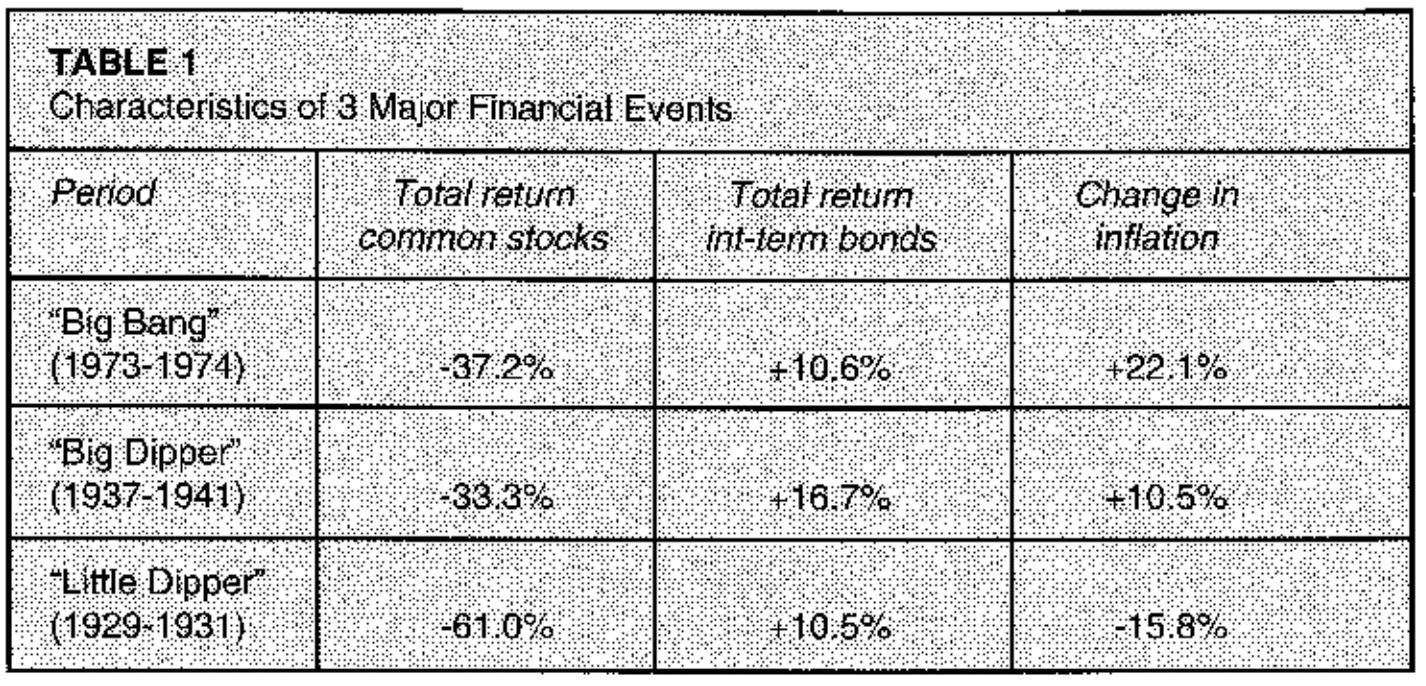

- While market returns are important, the 1973-74 recession was the “most devasting” according to Bengen due to the inflation that followed.

- The Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression were not as devastating because we experienced deflation.

- A 3% initial withdrawal rate survived at least 50 years in all retirement periods examined.

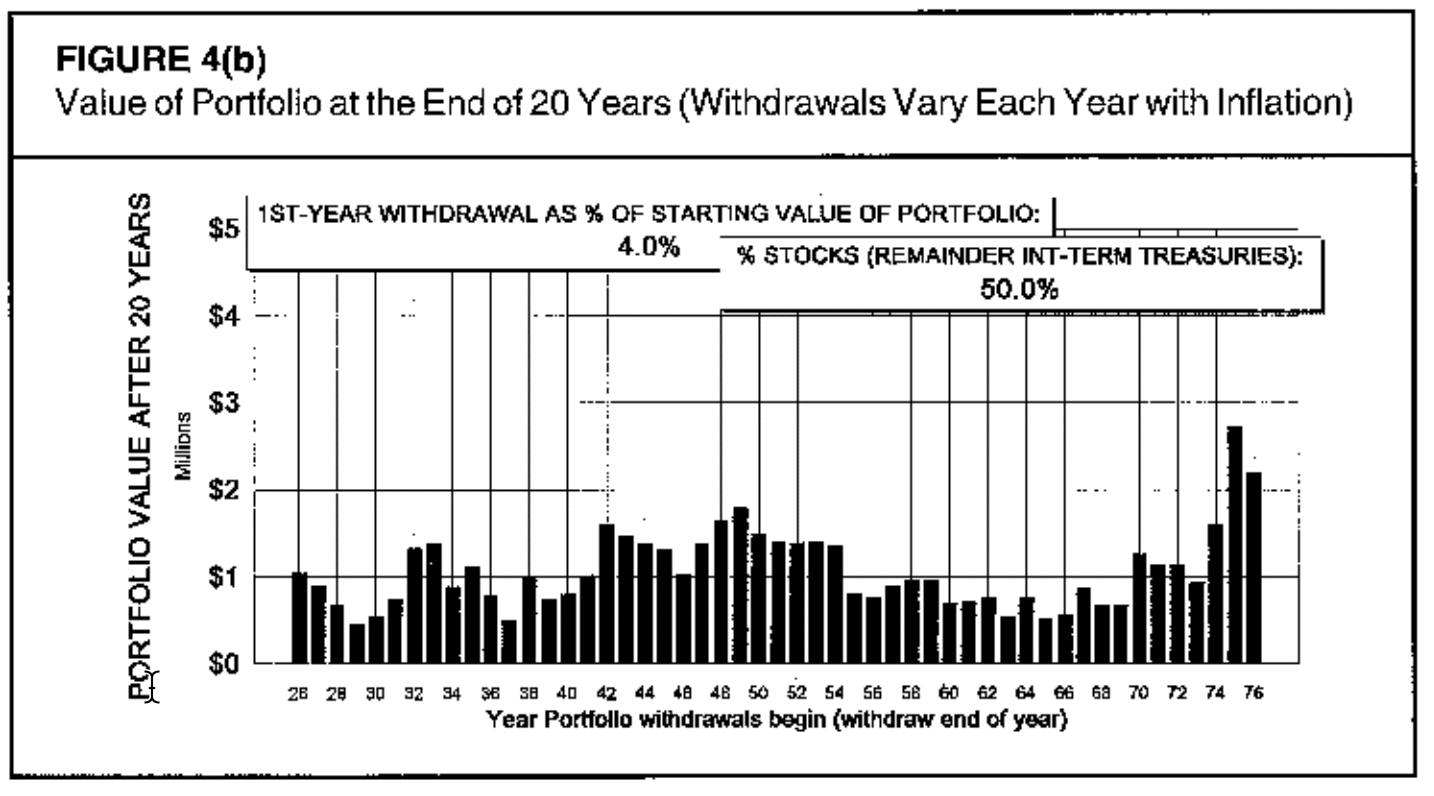

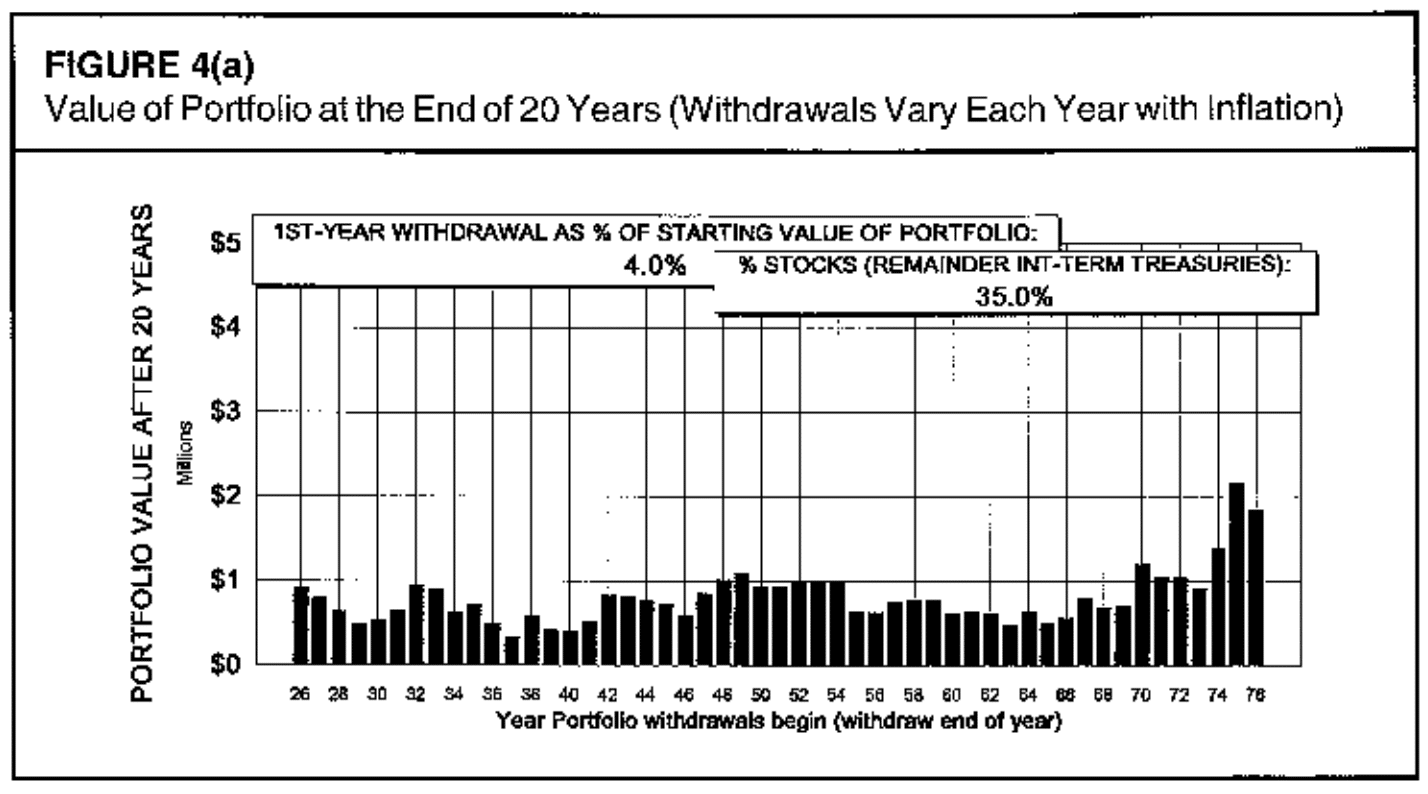

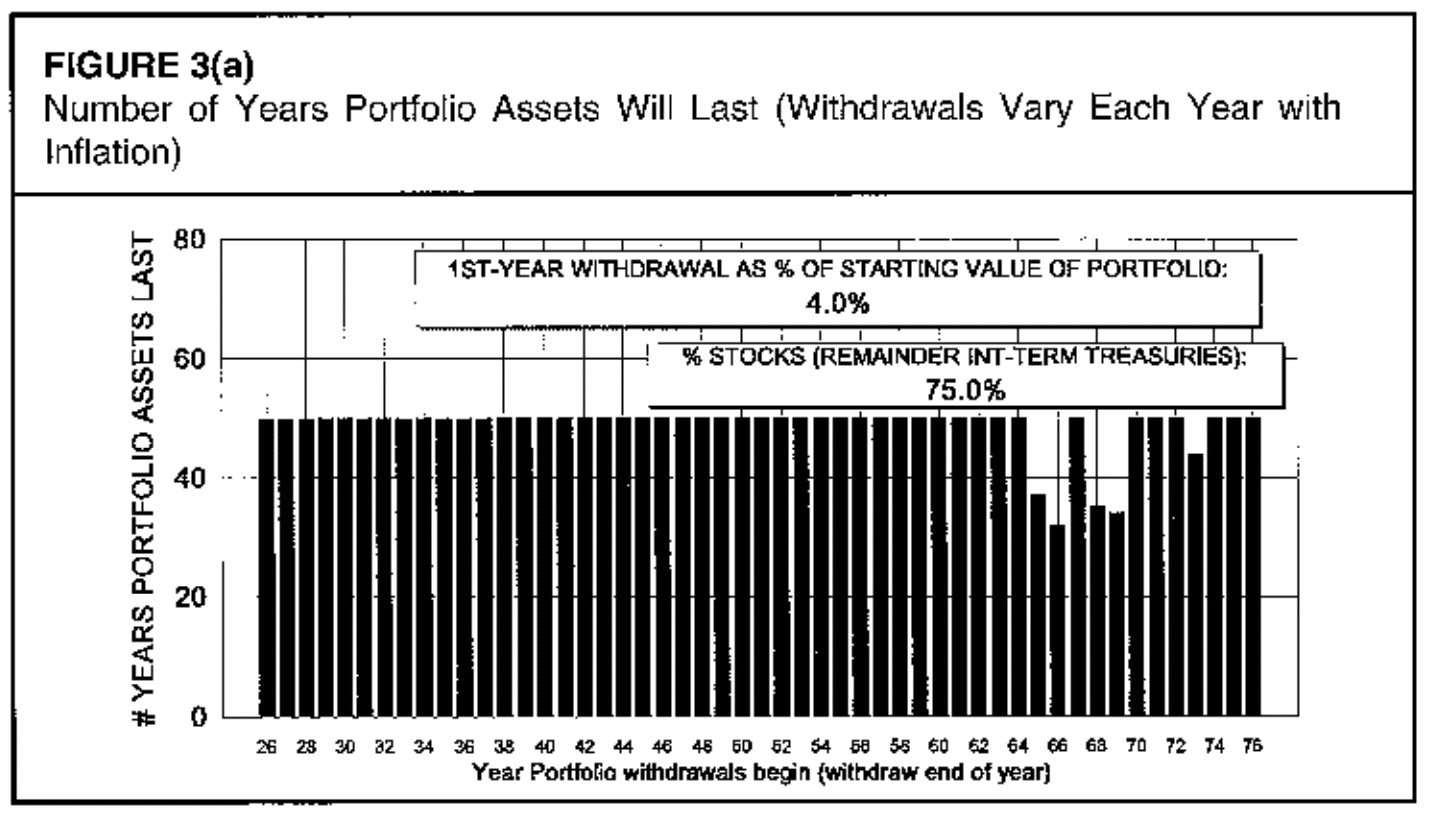

- A 4% initial withdrawal rate survived no less than about 33 years in all retirement periods examined.

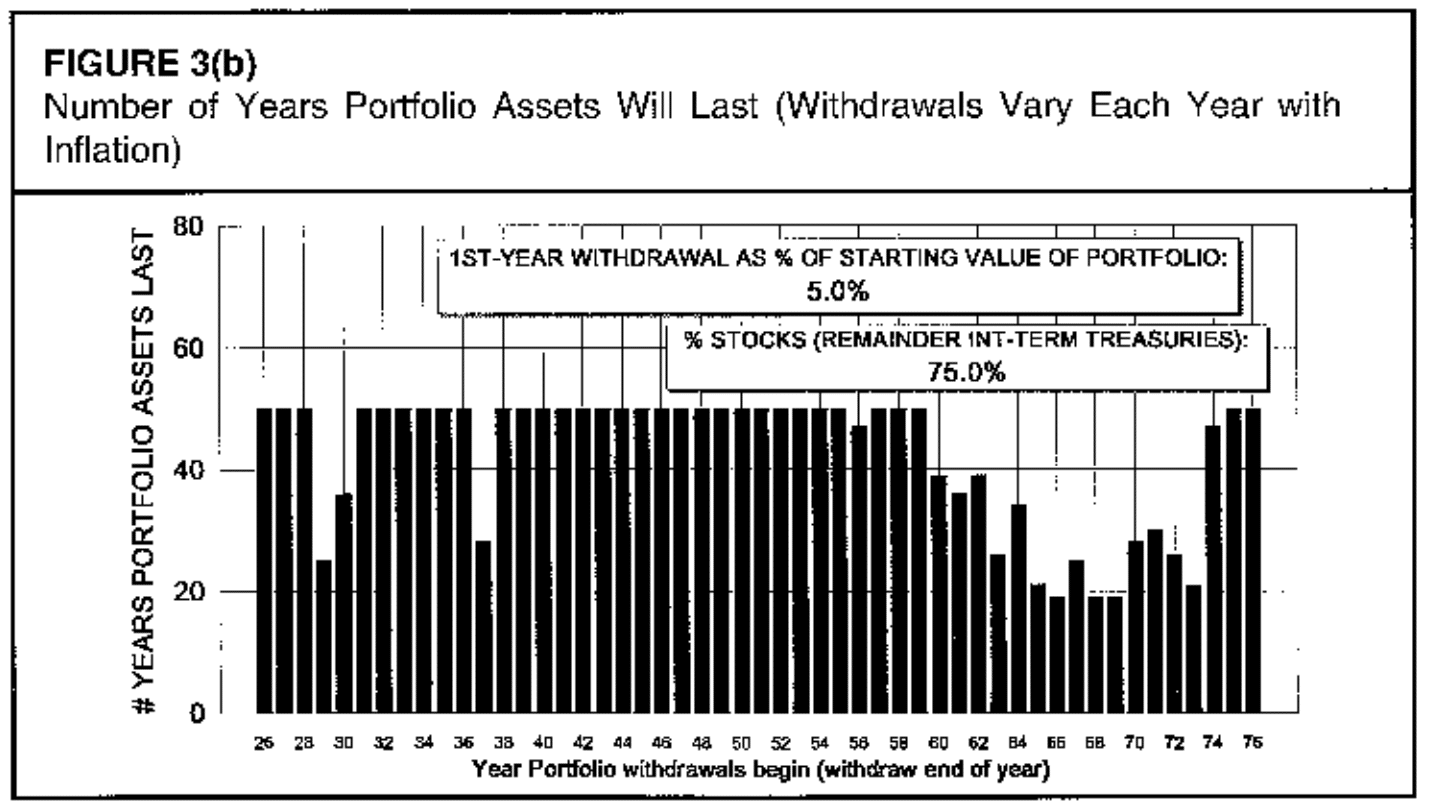

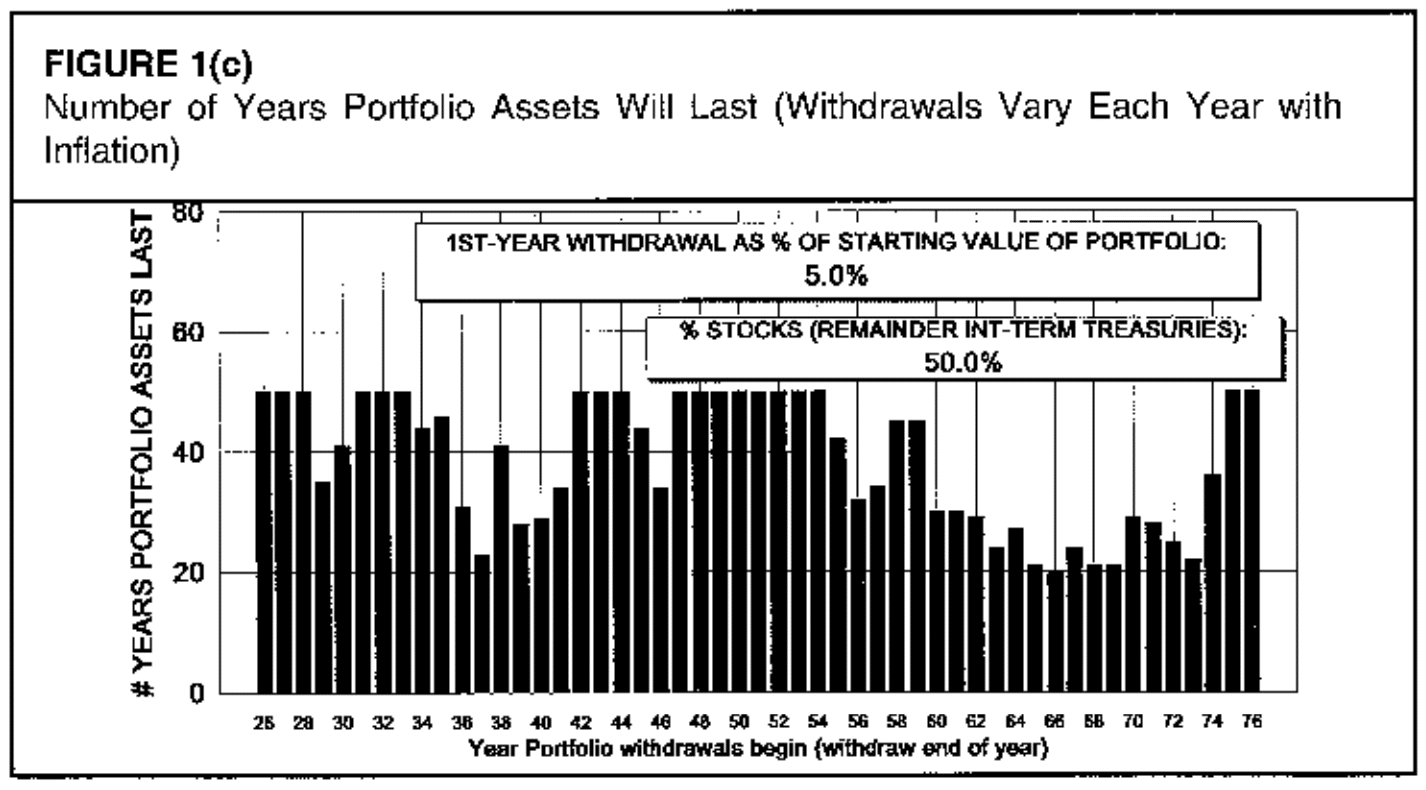

- A 5% initial withdrawal rate survived only about 20 years for those who retired in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

- The 1973-74 recession affected retirements that started nearly 20 years earlier.

- The “absolute safe” withdrawal rate is about 3.5%, which lasts at least 50 years. This is consistent with the idea of a Perpetual Withdrawal Rate.

- A 50/50 stock/bond asset allocation produces the highest SWR. In addition, holding too few stocks is more harmful than holding too much.

- A 75% allocation to stocks produces almost the same SWR as a 50/50 portfolio, and it also increases the retirement periods in which the portfolio lasted at least 50 years.

- In the end, a stock allocation as close to 75% as a retiree can handle is ideal.

- There is no need to change the asset allocation during retirement

- Reducing spending by as little as 5% just once during rough market conditions can go a long way to sustaining a retirement portfolio.

Key Quotes

“It is clear from Figure l(a) that an “absolutely safe” (to the extent history is a guide) initial withdrawal level is 3 percent, in that it ensures that portfolio longevity is never less than 50 years. (This is also true for withdrawal rates as high as approximately 3.5 percent.)”

“Assuming a minimum requirement of 30 years of portfolio longevity, a firstyear withdrawal of 4 percent [Figure l(b)], followed by inflation-adjusted withdrawals in subsequent years, should be safe. In no past case has it caused a portfolio to be exhausted before 33 years, and in most cases it will lead to portfolio lives of 50 years or longer.”

“I have not included charts for withdrawal amounts of seven percent and higher, as they are too high to be practical for the new retiree. His or her retirement capital would be exhausted very quickly in most cases.”

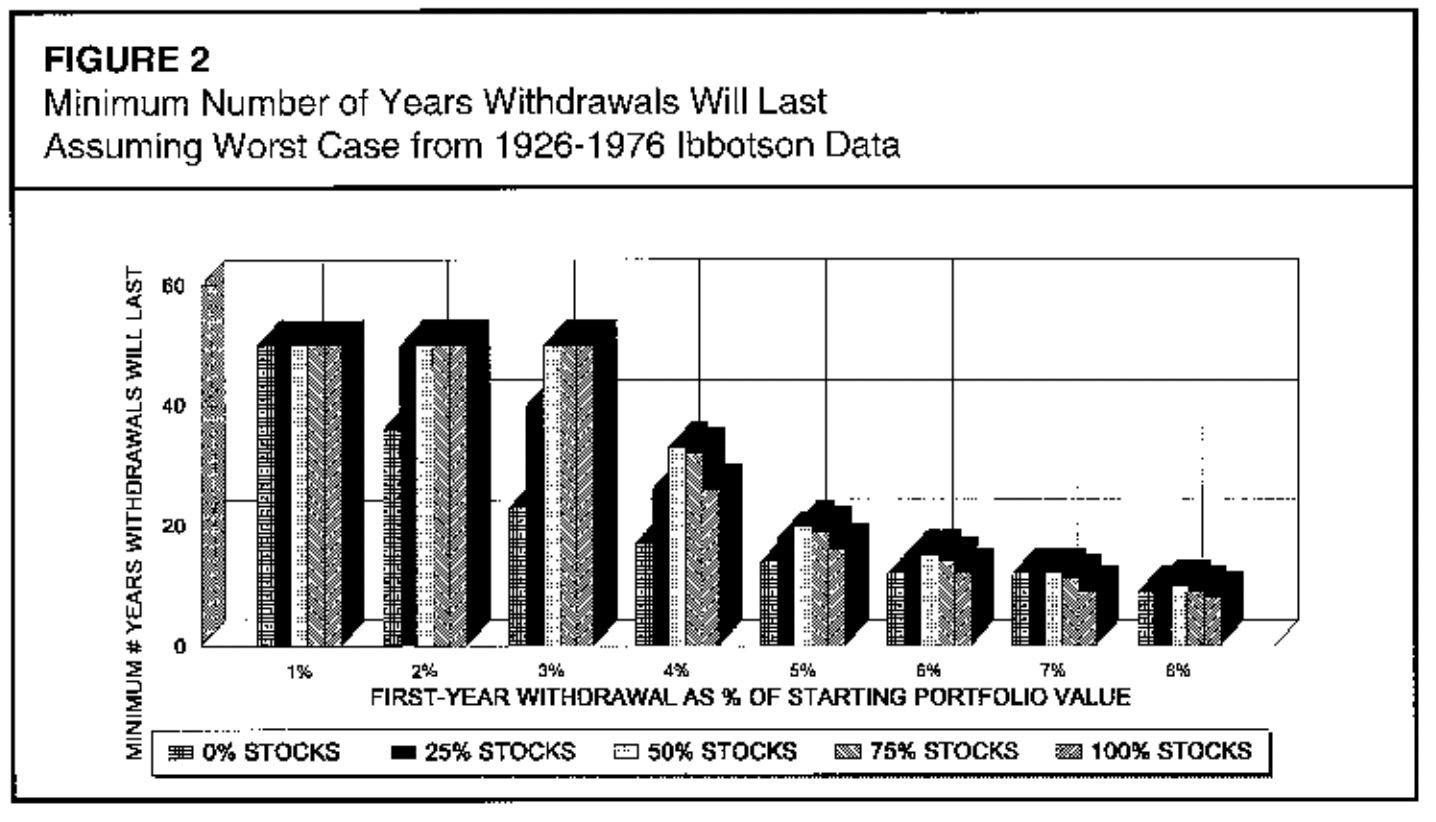

“One pattern that leaps out from the figure is that holding too few stocks does more harm than holding too many stocks. The “0-percent stocks” bar and “25percent stocks” bar are consistently shorter than the others, confirming what we already know the superior returns of stocks versus bonds are essential to maximizing the benefit from a portfolio. Too few stocks in the portfolio shortens the minimum portfolio life.”

“Perhaps even more important is the observation that the 50/50 stock~ond mix appears to be near-optimum for generating the highest minimum portfolio longevity for any withdrawal scheme. This is particularly clear in the 4-percent, 5-percent, and 6-percent withdrawal groups, which are peaked like roofs at the 50-percent stock level.”

“Does that mean that a 50/50 mix is optimal for all situations during retirement? Not at all. Note in Figure 2 that for all withdrawal percentages, the bars for 50-percent stocks and 75-percent stocks are very close in heightma year or less apart. From the perspective of the highest minimum portfolio longevity, that means you give up very little by increasing stocks from 50 percent to 75 percent of the portfolio. But do you gain anything in return?”

“Sorting this all out, I think it is appropriate to advise the client to accept a stock allocation as close to 75 percent as possible, and in no cases less than 50 percent. Stock allocations lower than 50 percent are counterproductive, in that they lower the amount of accumulated wealth as well as lowering the minimum portfolio longevity. Somewhere between 50-percent and 75-percent stocks will be a client’s “comfort zone.”

“What occurs when we increase stocks to more than 75 percent of the portfolio? This also turns out to be counterproductive. I have run an analysis on a number of scenarios using this assumption, and although accumulated wealth continues to increase, it is offset by the deterioration of portfolio longevity during the “Little Dipper” (Depression years). In fact, in most cases the minimum longevity during the Little Dipper drops below the minimum longevity established on the 50-percent chart (which occurred during the 1973-74 “Big Bang”), which is contrary to our objective of “making sure the money will last.” Therefore, stock allocations of more than 75 percent are to be avoided at the beginning of retirement.”

“My research indicates strongly that as long as the client’s goals remain the same, there is no need to change the initial asset allocation. It is likely to do more harm than good, as we shall see.”

“However, the client has another option to improve the situation for the long term, and that is to reduce–even if temporarily–his level of withdrawals. If the client can manage it without too much pain, this may be the best solution, as it does not depend on the fickle performance of markets, but on factors the client controls completely: his spending.”

“Despite advice you may have heard to the contrary, the historical record supports an allocation of between 50-percent and 75-percent stocks as the best starting allocation for a client. For most clients, it can be maintained throughout retirement, or until their investing goals change. Stock allocations below 50 percent and above 75 percent are counterproductive.”